Connecting Art and Humanities

DEEP DIVE: Mythology, Superheroes, and Personal Identity

by Richard Siegesmund, PhD, Northern Illinois University

The humanities investigate conceptions of culture—the linguistic, artistic, and philosophical roots that define specific social practices. They help us to understand where we came from and who we are. They also lead to speculation about who we might be and invite us to consider our creative potential. In this sense, the arts and humanities help ground us. They provide a context in which we situate ourselves, articulate our aspirations, and identify the supportive structures that sustain us. Most importantly, the humanities lay the framework for personal transformation.

Mythology

Myths are important to individual cultures and often provide subject matter and context for interpreting visual art. Artists tell stories that warn of danger and extol triumph. As metaphors, myths are often means for telling stories of the struggles for social justice and reliance against oppressive forces.

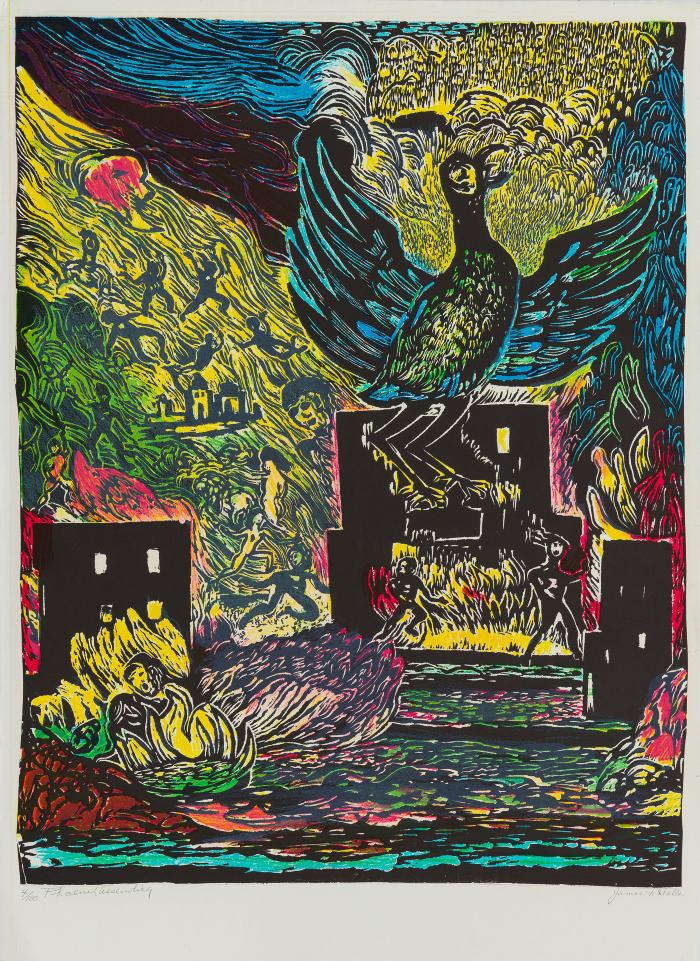

In his work Phoenix Ascending (figure 6), Artura artist James Lesesne Wells (1902–1993) appropriates the mythical bird the phoenix as a cultural reflection on the struggles of African Americans. On a regular cyclical basis, the phoenix, an enchanted immortal beast, burns to ash, but then magically regenerates itself to be born again. The original myth ascribes to ancient Egypt, but variations of the belief appear

Figure 6: James Lesesne Wells, Phoenix Ascending, offset lithograph, 30" x 22" 1985

in many cultures. The phoenix is a kind of ancient superhero with a superpower of living again after its own destruction. Looking closely at Wells’ composition, the phoenix rises out of a scene of flames and chaos. Bodies fall from the sky. Towering buildings blaze. Figures run in desperation. The catastrophic scene in the composition also evokes the Biblical prophecy that following the great flood in which God spared Noah and the creatures of the arc, God will one day return to punish the world by fire.

A professor at Howard University in Washington, DC, Wells had lived during the deadly urban riot of 1968, precipitated by the assassination of Martin Luther King, which devastated and impoverished large swaths of downtown Washington. The riots themselves were born out of historic patterns of systemic racial oppression that denied opportunity and basic human rights to African slaves and their descendants for centuries, and since the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, part of a 100-year strategy to contain and control the class system. Yet Wells offers a symbol of hope rising out of this ongoing anguish that spawned civil protests during the 1960s. The soaring spirit prevails.

Phoenix Ascending is a picture of tribulation and triumph that can directly speak to the life experiences of many diverse student populations that often have direct experience with hardship and struggle in their daily lives. However, what is often most educationally important in these stories—and of particular importance to students—are the aspects of resilience: how, like the phoenix, the student or the individuals close to the student find the power to not just endure, but to thrive. Like the phoenix, they are born again. Just like the title of Wells’ artwork Phoenix Ascending, we rise up. We overcome. These are stories that students would be eager and proud to tell. Placing such a story within the context of mythology would also allow students to explore how their individual experience falls within larger cultural contexts.

National Standards

The National Standards artistic process of Connecting calls on students to investigate the cultural contexts that inspire works of art. The online resource Encyclopedia Mythica offers students the ability to conduct their own research into myths of different worldwide cultures, thus supporting Anchor Standard 11.

The National Standards artistic process of Creating, Anchor Standard 1 suggests that an Enduring Understanding is for students to understand how artists shape their creative investigations. An Essential Question to support this is to understand how artists draw on the history of art to follow established precedents or break with traditions in pursuit of new, layered, and expressive possibilities. Wells draws on the myth of the phoenix to speak to urban issues that he has witnessed. How might students also repurpose a myth and, drawing from their own personal experience, find a way to repurpose a myth for their own personal expression?

Superheroes

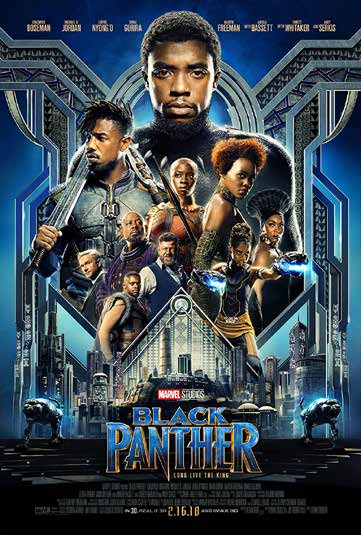

For their own creative work, students can appropriate myths from ancient culture, but they can also create new myths of their own. Consider the Marvel Cinematic Universe, which invents its own elaborate myths around the characters in its pantheon. In particular, the Marvel superhero Black Panther (figure 7) speaks to specific African and African American experiences as this superhero strives to improve his community and the lives of those around him. In a similar fashion, students might place themselves as a superhero into their own myths where—like the phoenix that overcomes suffering to live again or the Black Panther who intervenes to help others—students could imagine a superpower that would enable them to serve their community. As Marvel originally developed its characters for comic books, graphic novels could inspire students as an art form for expressing the new mythic narratives they are exploring.

Placing one’s own experience within ancient or new created myths leads to another National Standard for Responding, Anchor Standard 7 that challenges students to explore how their aesthetic engagement with a work of art “can lead to understanding and appreciation of self, others, the natural world, and constructed environments.” How might a myth that a student creates challenge us—inspire us—to productively and collectively live together? Returning to the idea of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, superheroes are more than powerful people with extraordinary abilities. They help people. The Black Panther brings communities and peoples together for mutual benefit. How could the student’s superhero come to the aid of others and build a stronger community that benefits everyone?

Wells’ Phoenix Ascending displays the superpower of the phoenix to regenerate itself from fire. The picture tells a visual story. Looking at the composition closely, one sees the phoenix revealing its mythical ability to rise in triumph, but you also see the fire and chaos that necessitates the bird’s rejuvenation. As the students look closely at the picture, ask them to pay attention to the visual facts in the picture. It is not enough for the

Figure 7: Marvel Studios, Black Panther, poster, 2018

picture to prompt the free flow of the imagination of the student. The students need to take the extra step of naming the visual facts in the picture that prompt their interpretation. What is the evidence in the picture to support their analysis? Then, how would students design a composition that tells the full complexity of their story? What visual facts does the student want to include in their own composition?

Curriculum Connections

Sample Proficiency Assessment Rubric for a Lesson Inspired by Phoenix Ascending

| Emerging | Approaching | Proficient | Exceeding | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Student researches mythology Connecting: Anchor Standard 11 |

Student struggles to frame a personal story into a possible mythological narrative | Student finds a myth by does little research | Student can connect one myth | Student explores connection or divergence in multiple myths from multiple cultures |

|

Student identifies a superpower Responding: Anchor Standard 7 |

Student's superpower is only for personal gain | Student’s superpower vaguely links to a community benefit | Student finds a myth but does little research | Student shows a clear and compelling narrative between a social problem and its solution |

|

Student creates a visual narrative from myth Creating: Anchor Standard 1 |

Student’s narrative is both visually and linguistically unclear | Student supplies a linguistical narrative but does not fully translate this visually | Student creates a compelling visual narrative from myth | Student blends two or more myths to elaborate their narrative |

Using Artura.org with the National Core Visual Arts Standards

The National Core Visual Arts Standards (National Coalition for Core Standards, 2014) provides an index of educational interventions for the comprehensive teaching of visual art in the K–12 classroom. Although comprehensive, the Standards can be overwhelming. A teacher might well wonder how they can be expected to teach all this content. When thinking about how to begin a lesson, educational researcher Robert Marzano (Marzano, Pickering & Heflebower, 2011) points out that student engagement with learning begins when they find a personal connection to the curriculum. Students ask, what does this lesson have to do with me? Why is it relevant? Why should I care? In short, a teacher needs to have student buy-in for the lesson if they are to have any hope of covering the aspirations of the National Core Visual Arts Standards. Therefore, in starting to introduce a lesson, a teacher would begin by turning to the National Standard’s artistic process of CONNECTING.

NATIONAL CORE VISUAL ARTS STANDARDS

Connecting

By exploring the imagery from Artura.org, teachers can discover opportunities for the work of significant diverse artists to relate to their students’ personal experiences and existing knowledge. Artura images can start conversations and relate to students’ cultural contexts. Anchor Standard 10 and its supporting Enduring Understanding ask students to investigate how images relate to personal experience: both the experience of the artist and the student’s own experience. Students can find their own experiences reflected in the visual choices and designs of the multicultural artists on Artura.org. The supporting Essential Question continues this line of inquiry into how art is more than personal expression but can give voice to community concerns.

ANCHOR STANDARD 10: Synthesize and relate knowledge and personal experiences to make art.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Through artmaking, people make meaning by investigating and developing awareness of perceptions, knowledge, and experiences.

ESSENTIAL QUESTION:

- How do people contribute to awareness and understanding of their lives and the lives of their communities through artmaking?

Many teachers in contemporary schools find it challenging to relate to the diverse cultural and life experiences of the students they encounter within a single classroom. Anchor Standard 11’s Enduring Understanding stresses the importance of respecting diversity and not trying to norm all students to a single common benchmark. Therefore, it becomes important to show work that demonstrates distinct cultural values and concepts of aesthetic composition. Artura.org allows teachers to explore cultural ideas through different cultural perspectives.

The value of this approach is for students to respect and admire differences. In the arts, this can be represented in diverse cultural conceptions of designs and color palettes— the variety of ways that we could think about “what is art.” Artura allows students to see the range of possibilities, a variety of narrative approaches to telling one’s own story, and ways we come together across a spectrum of distinct cultural contexts

ANCHOR STANDARD 11: Relate artistic ideas and works with societal, cultural, and historical context to deepen understanding.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: People develop ideas and understandings of society, culture, and history through their interactions with and analysis of art.

ESSENTIAL QUESTION:

- How do people contribute to awareness and understanding of their lives and the lives of their communities through artmaking?

NATIONAL CORE VISUAL ARTS STANDARDS

Responding

After connecting with a student, a teacher propagates a rich, creative exploration by allowing the student to RESPOND. This allows students to strengthen the links between their personal experience and the themes and issues raised in the work from Artura.org.

ANCHOR STANDARD 7: Perceive and analyze artistic work

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Individual aesthetic and empathetic awareness developed through engagement with art can lead to understanding and appreciation of self, others, the natural world, and constructed environments.

ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS:

- How do life experiences influence the way you relate to art?

- How does learning about art impact how we perceive the world?

- What can we learn from our responses to art?

This is a prime opportunity to engage students in the visual critical analysis of images: What do you see? What makes you say that? What more can you see? The student is looking for the visual evidence in a picture that shows how an artist built the meaning—the visual argument—in the work.

ANCHOR STANDARD 8: Interpret intent and meaning in artistic work.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: People gain insights into the meanings of artworks by engaging in the process of art criticism.

ESSENTIAL QUESTION:

- How can the viewer “read” a work of art as text?

NATIONAL CORE VISUAL ARTS STANDARDS

Creating

Having used the Standards for first Connecting, then Responding, the stage is set for CREATING.

Once a cultural/creative context has been fostered—one that allows students to place themselves in a broader framework that can be supportive of their creative thinking—there is permission to play with this context. You do not follow rules, you can disrupt and reconfigure contexts to better fit your own imagination.

Anchor Standard 1’s Enduring Understanding asks students to consider how artists both follow and break rules in the course of their investigations. The supporting Essential Question further elaborates on this by asking students why artists would do this.

In his 1988 print Crow Dance (figure 8), we see Native American artist Rick Bartow (1946–2016) both following and playing with his own cultural tradition. These works invite the students to engage in cultural inquiry into traditions to understand how artists follow and break with tradition

Figure 8: Rick Bartow, Crow Dance, offset lithograph, 30" x 22" 1988

ANCHOR STANDARD 1: Generate and conceptualize artistic ideas and work.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Artists and designers shape artistic investigations, following or breaking with traditions in pursuit of creative artmaking goals.

ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS:

- How does knowing the contexts histories, and traditions of art forms help us create works of art and design?

- Why do artists follow or break from established traditions?

Figure 9: Tomie Arai, Portrait/Young Woman, offset lithograph, 22" x 30" 1998

A second important reflective consideration that guides CREATING is found in Anchor Standard 2’s Enduring Understanding that works of art “define, shape, enhance, and empower” the life of the person who makes the images and the lives of the people who view and interact with the image. Works of art speak for whole communities.

Tomie Arai’s (born 1949) Portrait/Young Woman (figure 9), is from her series of portraits based on archival photographs of individuals and families of diverse Asian backgrounds—Chinese immigrants to the U.S., in this example—centering

“the experiences of people whose voices have not been heard.”

ANCHOR STANDARD 2: Organize and develop artistic ideas and work.

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: People create and interact with objects, places, and designs that define, shape, enhance, and empower their lives.

ESSENTIAL QUESTION:

- How do objects, places, and designs shape lives and communities?

NATIONAL CORE VISUAL ARTS STANDARDS

Responding

While CREATING, students need to respond reflectively to what the work is becoming. Earlier in the lesson, the students applied Anchor Standard 7 RESPONDING to the critical unpacking of the visual ideas in work from Artura.org. Now the students need to apply these same RESPONDING skills to their own artwork. Initially, this is a process of formative assessment.

A work of art is more than what the creator intended to do. A work of art has a life of its own. It responds to a creator’s intention, and the attentive artist listens to what a work of art itself wants to become. A final work of art is more than the sum of its parts. An artwork has its own living agency. This requires empathetic understanding as reflected in Anchor Standard 7.

Empathetic aesthetic understandings open us to new ways of contextualizing our life experiences as we communicate: speaking and listening to others. We begin to explore multiple layers of meaning—layers of meaning that may even be a discovery for the person who is creating the image. We begin to listen so that we can hear. In turn, this teaches us skills in how to speak so that we can be heard.

ANCHOR STANDARD 7: Perceive and analyze artistic work

ENDURING UNDERSTANDING: Individual aesthetic and empathetic awareness developed through engagement with art can lead to understanding and appreciation of self, others, the natural world, and constructed environments.

ESSENTIAL QUESTION:

- What can we learn from our responses to art?

NATIONAL CORE VISUAL ARTS STANDARDS

Presenting

As students complete a cycle of creating and responding, the teacher assembles multiple artworks together—either by a single individual or images drawn from across the diverse students in a class—so that patterns of artistic concerns may appear. Outlier responses are useful as these may even bring larger patterns into greater focus and open conversation.

Together, artworks preserve ideas, they make an argument, they ask for our consideration. What are the big issues that we take away? As we talk about a variety of artworks, how do we gain insight into how we might reenter our own personal work to push its communicative power further? The Enduring Understanding for PRESENTING, Anchor Standard 5 calls for students to consider how to revise their artwork so that it speaks clearly.

ANCHOR STANDARD 5: Develop and refine artistic techniques and work for presentation.

ESSENTIAL QUESTION:

- How does refining artwork affect its meaning to the viewer?

CURRICULUM CONNECTIONS

Building Lessons for Engagements

Following a structure of Connecting –> Responding –> Creating –> Responding –> Presenting, the National Core Standards can be employed to map out a path of student performance. In turn, the points of this pathway mark places where teachers can create proficiency assessments that can then create a rich portrait of student growth (see the Deep Dive chapter Art and Humanities: Mythology, Superheroes, and Personal Identity, featuring the work of

James Lesesne Wells, for an example of a standards-based proficiency assessment). The key to this performanceoriented curriculum and assessment strategy is student engagement. As Marzano states, it all begins with the student connecting to the lesson. Artura.org can be an invaluable resource for teachers to help the diverse students whom they teach to find points of entry into thinking in and through visual art.

References

Marzano, R. J., D. Pickering, and T. Heflebower. The Highly Engaged Classroom. Marzano Research, 2011.

National Core Arts Standards: A Conceptual Framework for Arts Learning. State Education Agency Directors of Arts Education (SEADAE), 2014. Retrieved January 2015, from http://www.nationalartsstandards.org/