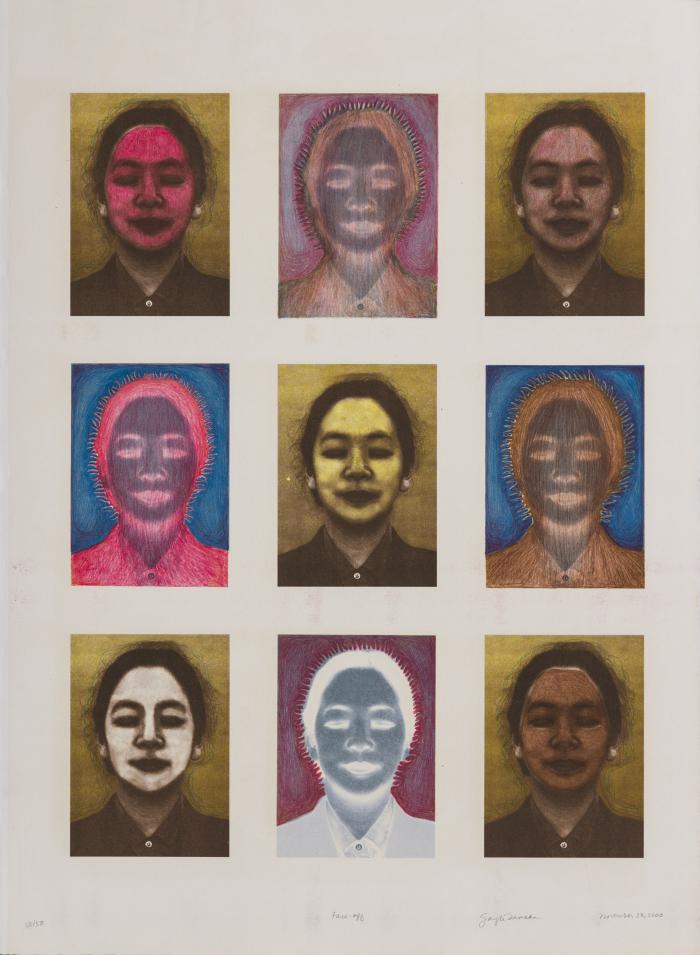

Face-Off

Gayle Tanaka

- 2000

- Offset Lithograph

- Image/sheet: 30 x 22"

- 50 prints in this edition

About the Print

From the Artist

As an Asian American woman, I work from the margins of America, mapping a family geography of immigration, assimilation, and internment. My work is, to a great extent, about appearance and what might or might not reside behind it. I was born in Chicago and grew up Japanese American in an otherwise Caucasian suburb. I grew up feeling like I was like everyone else inside, but with a face that made me different. Oddly enough, this difference made me invisible. My inner life was masked by my Asian face—no individuality, no identity other than the associations clustering around the shape of my eyes, the color of my hair, and skin.

It is the process of formation of what was/is behind my face that my work explores. Through the manipulation of imagery and color, I hope to reveal some of what goes on behind the changing face of America.

In the print Face-Off, I have taken my face and made it into a mask of color. Each of the nine faces shows a tonal variation that in life would connect the face with an ethnic group and all the associations attached. In the print, the tones are simply layers of ink on a piece of paper, just as skin is a layer of tissue on other tissue. How can this superficial layer have acquired such importance and meaning, such profound and often tragic social and historical consequences? Red people, black people, brown people, yellow people, white people—find a person who is actually red, brown, yellow, black, or white—most are shades of pink and brown. Yet, the flagrant inaccuracy of these classifications can in no way mitigate or lessen past and present pain and suffering caused by the hierarchical imposition of social structures based upon them. So, we must continue to remind everyone that what is under the skin, under the ink is something different, individual, yet always the same—a human being—a face behind which reside a life lived, living, and to be lived. And however it is lived, a life that should not be limited, oppressed, or [in] any way altered due to the hue of its most superficial component.

—From Brandywine Workshop and Archives recordsThese are self-portraits, those are images of myself in the print. I use self-portraiture often as a basis for my work. Through manipulating images of myself, I’m able to both investigate and make statements concerning how this self is developed and defined both individually and culturally. Growing up as an Asian American in the Midwest, I learned at an early age that my parents attracted attention and that I was different, and my work often involves this feeling of difference and everything that stems from it. I was making a statement about the presentation and perception of my face…the physical layer of my identity, so by changing colors overlaying design and adding markings to these images of myself, I was presenting multiple versions of myself by presenting these multiple versions of my face.

—Adapted from interviews conducted by Drexel University students, supervised by Jen Katz-Buonincontro, PhD, 2021–2022

About the Artist

Artist and printmaker Gayle Tanaka earned her BFA in painting from the University of Hawaii and an MFA in printmaking from San Francisco State University.

She has exhibited her work nationally at institutions including SOHO20 Gallery, Brooklyn, New York City; El Museo, Buffalo, NY; ARC Gallery, Chicago Cultural Center, Hyde Park Art Center, and Anchor Graphics, Chicago, IL; A.I.R. Gallery, New York City; San Francisco Art Commission, Olga Dollar Gallery, Contemporary Jewish Museum, and Japantown Peace Plaza, San Francisco, CA; Noyes Cultural Arts Center, Evanston, IL; Newhouse Center of Contemporary Art, Staten Island, New York City; Center for Photography at Woodstock, NY; Honolulu Academy of Arts, HI; and Rice Media Center at Rice University, Houston, TX.

Her awards and residencies include a BCAT/Rotunda Gallery Artists’ Residency in Brooklyn, New York City; Knight Foundation Visiting Artist Fellowship at Brandywine Workshop and Archives, Philadelphia; Anchor Graphics artist residency, Chicago; Puffin Foundation Grant Award; and a Kala Fellowship Award, Berkeley, CA.

—From Brandywine Workshop and Archives records

Curriculum Connections

Suggested Topics for Literature and Creative Writing

Creativity in response to Oppression

Marginalization, a form of oppression, assumes that an individual’s ability to perform a job is determined by their identity (Latin Americans are gardeners, African Americans are domestic servants, women are clerical assistants—while Native Americans are not seen as individuals, living human workers but as symbolic mascots for sports teams, etc.). In response to oppression, artists marshal their creative work as forms of resistance. Leaders like Martin Luther King advocated that the most potent forms of resistance were nonviolent. The arts are especially effective forms of nonviolent resistance as they give voice to the human spirit, emphasize our shared humanity, present startling juxtapositions by showing how oppression creates brutal realities for some and pleasure for others, and inscribe iconic aesthetic images that reverberate in our contemporary awareness and historical imaginations. Let’s explore how we feel about ourselves and our community role based on our passion, talents, background, and location.

Questions to Consider

- How do we define ourselves?

- In what ways do others define us?